Update: now available in Czechoslovakian!

The weekend before last (22-23rd February) was the culmination of the Jollablot Viking Festival in York. Due to the large amount of re-enactors present and the various battles that went on, there are quite a few photo-sets doing the rounds on facebook, flickr and so on. As I didn’t go I decided to have a glance through some of the galleries just to see what I missed. Fortunately one of the things I missed was boar tusk necklaces – one photo has a large mailed warrior with a pair mounted in bronze and dangling at his neck, another has a trader behind his stall with a silver mounted one, another warrior combines the two and has a pair mounted in silver rather than nasty bronze.

Why is it fortunate for me that I missed this? Well, as someone who is slightly obsessive about all things boney and historical (particularly of a Viking/Saxon kind), boar tusk necklaces feature quite highly on my “ARGHH!!!! NO-NO-NO-NO-NO!!!!” list. Somewhere in the dim and distant past of re-enactment, someone decided they looked “cool” and “manly” and that idea has stuck. This is despite the fact that there is no evidence to back this up.

“Poppycock!” I hear warriors shout from all over the internet, “of course they had boar tusks!”. Alas, it is not so, and as this is not meant entirely as a rant but also as an educational post, I will show the (lack of) evidence for boar tusk necklaces during the Viking and Saxon period.

If you don’t want to read the whole post (chicken!), jump to “Conclusions“

Before the Saxons

Prior to the pagan Saxons arriving in Britain, the general culture of England was an amalgamation of remaining pre-Roman traditions, imported Roman culture and in certain places elements of other European cultures that had been brought here by auxiliaries and so on with the Romans.

During this period, it would not be entirely uncommon for boar’s tusks to be found as ornaments, singly or in pairs, and either mounted in metal or simply perforated. Examples from Britain include (but not limited to);

- Scole – A roughly trimmed and perforated boar tusk, dated 3rd-4th century (Wade-Martins 1977, 203-204).

- Richborough – a pair of boar tusk mounts, each originally comprising two tusks held together by a central bronze mount (Bushe-fox 1949, 141-2, pi. XLVI, 173-4).

- North Wraxall – A pair of boar tusks found in a similar mount to those from Richborough. Dated 1st-4th century AD (Chadwick-Hawkes 1961, p29)

These traditions were a reflection of the rest of Europe, and similar mounts are known from the same period, particularly used by Germanic mercenaries (MacGregor 1985, p109) and have been variously interpreted as mounts for shields or helmets, or even horse fittings (Meaney 1981, p133).

Saxon

Use of boar tusks, and boar imagery, continued into the early pagan Saxon period and is probably an import of the traditions of the Germanic peoples themselves rather than an adoption of pre-existing beliefs. As early use of such amulets appears in the Eastern Mediterranean and then is adopted by the Romans, it has been suggested that the Germanic peoples in turn adopted the practise from the Romans (Meaney 1981, p133).

The boar features both in literature and wargear of the time. The early Saxon helmets from Benty Grange and Wollaston (“Pioneer” helmet) both feature boar crests, the Sutton Hoo helmet also has boar figures, and the epic poem Beowulf (set in the 6th-7th C) describes “….. the boar-sign that stands on the helmet” and the boar image on a banner. Clearly the boar remained an important symbol of the warrior and battle.

However, while the boar as a symbol was apparently widely used by warriors, physical elements of the boar do not appear to have been treated in the same way.

There are a number of boar’s tusks found in pagan Saxon graves and there are a few features common to all of them;

- They are found in graves dating to the 5th-7th centuries.

- They are usually found singly (sometimes more than one in a grave, but not as mounted pair in the way the Roman examples were)

- They are never mounted in precious metal (they have either a simple perforation or a bronze mount).

Necklace from female grave at Wheatley with a boar tooth and two canid teeth (Image after Meaney 1981)

A further point that needs to be made, is that with the exception of two very early examples, the graves are also exclusively female (as in the image above) or those of children . The two burials that are the exception are Stowting in Kent, and Kemp Town in Sussex. Both were excavated during the 19th century and as was the way of many excavations then, the “report” for each is little more than a brief list of roughly what was found, and less a serious and detailed account of the excavation, additionally skeletal identification was sometimes rather hazy (hence reports of men with big brooches i.e. tortoise brooches).

Stowting is the site of an early Anglo-Saxon cemetery that was dug by various individuals during the 19th century. One particular report from 1883 describes a male burial that contained a spear and a langsaex along with a comb and “a piece of a boar’s tusk worked” (Brent 1883, p85). The position of the remains however suggested to the excavator that the body had been seated and then as it decayed it collapsed or slumped. This means that the tusk was found in the vicinity of the skeleton but there is no evidence to suggest how it was used by the individual.

Kemp Town is an Anglo-Saxon barrow that was excavated in 1837. The report describes a male burial that was found with a sword, spearhead and a boar tusk ,as well as some horse bones (Meaney 1964, p251). However, as with Stowting there is a lack of information regarding the exact find spot and it is not assumed to be amuletic (Wilson 1992, p108-109).

Stowting and Kemp Town have both been given a date of the 6th century, implying that the burials within represent either the first wave of settlers or first generation children of those settlers – either way they still have very strong ties with the Germanic culture of the Late Roman period. Also, both Kent and Sussex are within the area of England that shows most evidence of influence (or settlement) by the occupants of the Near Continent and so are most likely to have connections with such customs (Meaney 1981, p133).

Viking

Unlike the migrations of Germanic settlers to Britain that appear to have brought some of their customs with them, Scandinavia never saw such a movement of people. Instead, it would appear that the burial practises there remained stable from approximately 200AD – 1000AD (Kovárová 2011, p83) and that unlike England, boar tooth pendants appear to be lacking in Migration period and Viking Scandinavian burials.

Recently two studies have been carried out: one on amulets of the Viking age (Jensen 2010) and the other on the significance of the Boar/pig in Old Norse culture (Kovárová 2011). It is telling that in neither of these are boar tusk pendants really discussed in depth. Indeed, when discussing finds from graves, Kovárová has to resort to Stowting and Kemp Town in order to cite examples from male burials of pendants as Scandinavian deposits appear to to be of skeletal elements rather than teeth (p83-85).

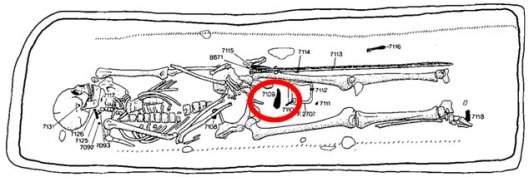

However, there is one burial from England that is repeatedly cited by re-enactors as proving that Viking warriors wore boar tusks – Repton. A few of oft quoted facts about Repton are true; it is a Viking warrior grave, it does date to mid-late 9th century, there was a boar tusk found there. The main “fact” that I get told however is totally made up – that the boar tusk was a necklace. In the image below, the position of the boar tusk in the grave is shown by the red circle.

Viking warrior grave from Repton, boar tusk is circled in red (Image Biddle and Kjolbye-Biddle, 1992)

As can be seen, the tusk was actually found between his legs and nowhere near his neck, and while components of necklaces do migrate slightly in graves as the body decays, they end up in the chest cavity or above the shoulders rather than between the legs. Further telling aspects of this tusk are the fact that the tusk is actually broken (possibly when removed from the jaw) and shows fire damage, and that it has no sign of a mount or suspension hole. Additionally, the man died violently, with a blow to the head, followed by a slashing cut to the inner left thigh and possible disembowelment (Hadley 2008, p274). The thigh cut would have also have removed the genitals and it is presumed that the tusk is seen as replacement for burial so the warrior can be sent on his way intact (Richards 2003, p386, Hadley 2008, p274, Jenson 2010, p175-176). There is no indication or suggestion that this is part of the man’s necklace, the primary component of which would probably have been the silver Thor’s Hammer also found in the grave.

Conclusions

Boar tusk pendants and mounts are known from antiquity. However, in Western Europe, they are restricted to the Roman period and very early Post-Roman/Pagan Saxon period.

Beyond the 6th century, all known examples are found in female or children’s graves, and they are simple affairs of a single tooth, either perforated or with a bronze mount. The twin mounted boar tusks, or clad in silver etc are either an appropriation of earlier, Roman examples or are a totally made up re-enactorism.

I have been unable to find any examples of boar tusk necklaces associated with warriors from anywhere in the Viking world throughout the so-called “Viking Age”, and given the large numbers of other pendants known e.g. Thor’s hammers are found in over 250 graves or cremations, it seems exceptionally unlikely that tusks were ever worn by Vikings of either gender, let alone male warriors.

Regarding Traders….

In light of the fact that many people sell these as “Viking”, and it is possible that I could have missed a known example, I contacted every trader I could find who sells boar tusk pendants/mounts and asked for provenance.

Without fail I either got no response whatsoever or was told it was “based on” something – usually a bracelet from a hoard and the trader had simply made a Roman style mount and decorated it with Viking style decoration. In short, not one could provide an actual find site from anywhere in Europe for Viking boar tooth pendants.

Sources:

Brent, C., 1883, Notes of Anglo-Saxon discoveries at Stowting.

Bushe-Fox, J. P., 1949, Fourth report on the excavations of the Roman fort at Richborough, Kent, Oxford: The University Press; London: The Society of Antiquaries, Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London 16,

Chadwick-Hawkes, S., 1961, Soldiers and Settlers in Britain, Fourth to Fifth Century. Medieval Archaeology, 5 (1961): 1–70

Hadley, D.M., 2008, Warriors, Heroes and Companions; Negotiating Masculinity in Viking-Age England. in Crawford, S. & Hamerow, H., (ed) “Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History 15”. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

Jensen, B., 2010, Viking Age Amulets in Scandinavia and Western Europe. Oxford: B.A.R. International Series.

Kovárová, L., 2011, The Swine in Old Nordic Religion and Worldview. Unpublished MA thesis

MacGregor, A., 1985, Bone, Antler, Ivory and Horn: The Technology of Skeletal Materials since the Roman Period. London, Croom Helm.

Meaney, A. L., 1964. A gazetteer of early Anglo-Saxon burial sites.

Meaney, A. L., 1981. Anglo-Saxon Amulets and Curing Stones. Oxford: B.A.R..

Richards, J.D., 2003. Pagans and Christians at the frontier: Viking burial in the Danelaw. In: Carver, M.O.H., (ed). “The Cross Goes North: Processes of Conversion in Northern Europe, AD 300-1300”. York Medieval Press in association with Boydell & Brewer, York/Woodbridge, pp. 383-395.

Wade-Martins, P. (1977). East Anglian archaeology. Report no.5, Report no.5. Gressenhall, Norfolk Archaeological Unit (for) the Scole Committee for Archaeology in East Anglia.

Wilson, D. R., 1992. Anglo-Saxon Paganism. s.l.:London, Routledge.

*if you haven’t figured it out by now, the title is nothing more than a bit of silliness based on the fact that as a male Viking era re-enactor wearing a boar tusk necklace (particularly a double tusk one) you may be an out of time horse or female Saxon but you certainly are not a manly Viking warrior. Certainly gets peoples attention when you say it to them! 😀

Excellent! Boar tusk jewelry for you seems to be up there with leather belt straps for drinking horns with me.

🙂

There is a whole host of things up there for me 🙂

Heavily painted leather, intricately tooled sword scabbards and belts, leather hanger for horns, metal belt rings for axes,leather loops for swords, heavily carved drinking horns, boar tusks…..the list rather goes on and basically encompasses everything re-eanctors do “because its cool and I like it” rather than doing because of actual evidence. 🙂

If I was religious, I’d say, “Amen, Brother!”

🙂

I’m with you on the tusks. Necklaces of big amber chunks and or glass beads on the “manly warriors” is what I see here in the states. I think it was two beads as the largest amount ever found in a Scandinavian Viking age male grave, and even that was a rare enough find to make them a novelty. Every time I see a guy wearing them I think to myself, “Is he portraying some sort of half assed transvestite?”

Offenders that cite Ibn Fhadlan as provenance for Viking warriors wearing large amounts of beads then need to be reminded that the Northmen in the account are described as collecting large amounts of beads that were stowed on the ships and then given to the women to wear.

Thank Chris. Until recently the most beads in a male grave that I know of was 3, but the site at Cumwhitton, Cumbria has just been published in the last few weeks (getting my copy on Sunday) and I believe one had 5 (or 7?) beads, will check on Sunday when I get the book and let you know.

That would be great!

One of the male graves had 6 beads and 3 silver rings, all probably forming a necklace.

Pingback: Did Viking men wear necklaces? | Halldor the Viking

Thamks for this. I wish there would also be an article about beads worn in beards. In germany it’s almost an epidemic to have beads in beards. Some guys even braided their beards and wear about a poundnof silver in it. It’s not only one bead but 10 or 20. For me it’s ridiculous and pure phantasy but when you ask them abou this they always have an answer like: a bead was found around the neck. Can you prove it’s from a necklace or a beard? Can’t hear it anymore. It’s always the same stupid discussion. So I would be happy if someone could end this with an article like yours about silly boar tusks

It is like a bronze age sprang braided cap worn by Viking women. IT IS JUST WRONG!

Pingback: It’s been a while…… | Halldor the Viking

Hi, please see the third photo from the top on this page:

http://bukowlas.blogspot.com/2012_07_01_archive.html

under no 9 it says “amulets from boar an bear tusks”. These are items from Opole – Ostrówek. I do not claim they were worn as necklaces, I didn’t read the related literature yet, but I believe these are artifacts from early medieval period.

Hello,

They may be Early Medieval in date, but that still leaves many other questions before they could be used as evidence to support male Vikings wearing them as necklaces.

Many graves are known to have animal tooth pendants, just not male Viking, so I wouldn’t be surprised to find that these were from a burial and part of a necklace, but I would be more surprised if the burial wasn’t female and local 😉

The wearing of animal tooth pendants pre-dates the Viking Age and follows it, but for different reasons. One of the reasons in the 11th C and onwards is as a reaction to Christian expansion, which is what has been suggested for various finds from Estonia (that also happen to be found in the graves of women or children rather than warriors).

So I don’t disagree that the image you link may show teeth as pendants, that has never been disputed, but it doesn’t in anyway support the theory that male Vikings wore them.

The tooth labeled 9 on the third picture is not a boartusk. It is indeed a tooth but from a carnivore.

regards Leif, archaeologist & reinactor

Great post. I think the reinactment community have some serious problems with merchants trading goods that sell rather than what is historically correct.

I also think the the reinactors should go to the sources (archaeological finds) rather than copying other cool looking reinactors.

Pingback: Náhrdelníky z kančích zubů | Projekt Forlǫg